by Nathan Stout from AccordingToWhim.com

Welcome to Game Board Review Week here on the According To Whim Blog. We have chosen seven of our favorite games to review and tell you about. Here is the layout for the week in case you will be interested in reading more!

- Monday – Clue Mysteries

- Tuesday – NetRunner

- Wednesday – Rockettville

- Thursday – Mastermind

- Friday – Key Harvest

- Saturday – Mad Magazine/ Facts In Five

- Sunday – Chris’s Surprise Game Review

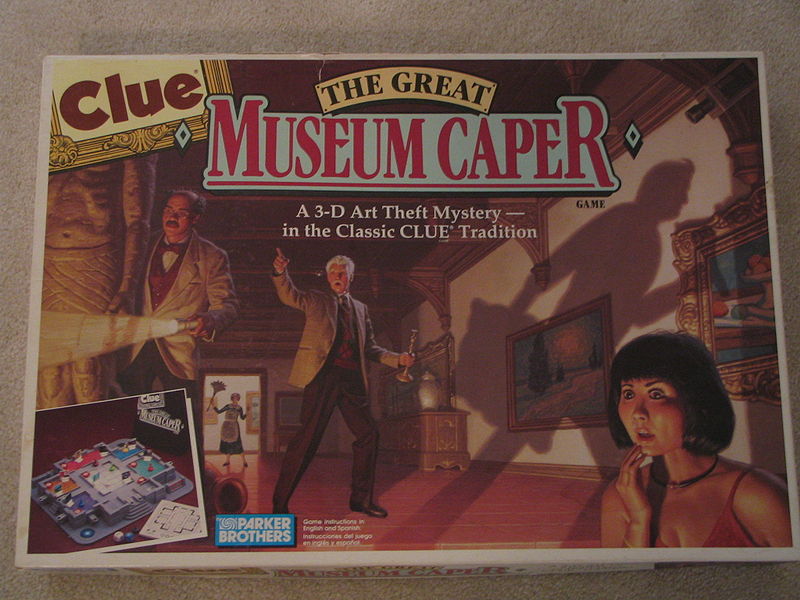

Today I will be covering “Clue: The Great Museum Caper.” Unless you are an avid game board player, you might not have heard of this entry into the Clue series of games.

Released in 1991 “Clue: The Great Museum Caper” arrived and quickly vanished off the scene, even though it was awarded a place in the 1991 Mensa Select list of board games.

Perhaps this Clue game wasn’t as popular because no one gets knifed or bludgeoned in it. That’s right, there are no murders here, just theft. “Clue: The Great Museum Caper” is about the theft of famous paintings out of the Body Museum. Yes, Mr. Body had a museum.

Players choose one of the Clue characters, or they choose the thief. The Clue characters move about the museum trying to land on (and thus capture) the thief, while the thief moves about and tries to steal famous paintings without getting caught. Sounds simple enough, but there are a few twists thrown in.

- The thief is invisible (until spotted).

- The thief can thwart the characters and their ability to locate him.

- The thief can escape at any time and win (as long as he has stolen at least 3 paintings).

The games runs thusly: The characters place locks on the windows and exits to the 3D museum board (some locks are unlocked and some are locked, only they know). Then the characters place several surveillance cameras in strategic locations in hopes of catching the thief later. Finally, the characters place the works of art and themselves in the museum. Once done, the player who is the thief denotes all the locations of the art and cameras on a pad he keeps hidden behind a screen. He then writes down where he is ‘at’ on the pad.

That’s right, only the thief knows where the thief is at any given time, so if your buddies are no-good liars you might not let them play as the thief. The thief gets three spaces to move each turn. They denote where they moved on their pad, and then the player’s characters move by rolling a die. The thief can even move through character spaces (he just can’t end his turn on them).

Now some of the fun comes from the extra die rolled by the characters. It has several symbols on it, including a camera and an eye. The player rolls the die with the movement die, and when certain symbols come up, they get extra actions to preform. One of the actions is the ability to use the cameras they placed at the first of the game. They can specify if a particular camera can see the thief. If it has this helps narrow down where the thief is on the board. Another symbol stands for a motion sensor, and the player can ask on what color tile the thief is on. This will also narrow down where the thief is at, however the thief has a couple of chances to ‘cut’ the motion sensor wires and decline to answer. The thief can also disable the cameras as well or even cut the power to the building (by visiting a special square on the board). These things will slow the characters down in their search for the thief.

The thief’s main goal is the theft of as many of the works of art as possible (with a minimum of 3) and to escape the building (through a window or door). The player who is the thief will end his turn (on a space with a painting) and on the next turn (after they have moved) they remove the painting off the game board and keep it. This lets the players know a painting has been stolen and narrows the location of the thief.

Like I stated earlier the thief if invisible until he is spotted by a character or a camera. The other symbol on the extra die allows for a character to look (within it’s line of sight) and see if they can spot the thief. If they can see the thief (aka the thief is on a space that is horizontal or vertical to the character’s pawn, any distance away) he becomes visible and the player must place the thief pawn on the game board. There is no going back to being invisible once you are spotted. At this point its brown trousers time for the thief, as he must work fast to steal more paintings and escape.

Once a thief has a minimum of three paintings, he moves to an exit (a window or door) and tries the lock. A player flips the lock over, and it shows if the exit is locked or unlocked. If locked he must move to another exit and try that lock, if its unlocked he moves out and the round ends. If a thief is caught (one of the other player’s pawns ends a turn on the space where the thief is) then the player playing the thief loses.

The next player is now the thief. All paintings and cameras are replaced, and the game is played again. Whoever gets out of the museum with the most stolen paintings is the winner.

This game has elements similar to “Scotland Yard” (the invisible player motif) and will run you about thirty minutes per round. Chris and I have enjoyed this game several times, but often we get busted before even getting the minimum 3 paintings. It is a challenging game, but I think the whole invisible player concept will confuse younger players. If you are wanting to teach someone “Scotland Yard,” this might be the place to start. It has a much simpler board and has the same ‘invisible’ game theme.

The board itself is injected molded plastic, and has a lot of nice little details. I really like 3D game boards, and I think this is one of the best. If you want to see my review of this game check it out on YouTube here.

Strategy: Here are few strategy points that Chris and I have tried (with varying success).

- Don’t go after the paintings right away, knock out as many cameras as possible.

- Cut the power to keep the characters on the move.

- Shadow the characters, they won’t expect that.